|

|

|

|

On The Trail of the Gray Ghost August 8, 2021 Photos and text by Dave Parsons There is something exhilarating about exploring a wilderness that is full of grizzly bears. Being part of the food chain heightens ones senses and physical awareness. As I studied whose footprints remained in the mud along the trail, I was armed only with my wits and a handy can of bear spray. Ready as ever for any potential encounter, I thought of potential bear-eating-human cartoon lines, many from the Far Side strip. I tried to come up with my own - While gnawing on my toes one bear says to another 'they definitely need more seasoning, Vern, grab his pepper spray.' In the days after the glaciers retreated and humans hunted and gathered in unexplored lands, they at least had more tangible forms of self defense. A spear, atl-atl, bow and arrow, club or even a big knife sounded better than a potentially malfunctioning can of bear spray, or my Leatherman Tool that I could use the pliers and ply a bear to death. And no, guns are not allowed in Canadian National Parks. It was only a couple of months ago that my wife Anna and I ran along this stretch of trail along Portal Creek in Alberta’s Jasper National Park. We had no issues, however, their were plenty of big bear tracks squished into the mud along the trail. Starting the trail alone on this early September day made me feel a bit vulnerable, I guess I could have carved a pointy end on walking stick, but why bother, too much trouble to carry. Unfortunately, I’m also one of those people that doesn’t always follow the backcountry ‘safety rules.’ I enjoy hiking, running and backpacking alone rather than traveling in a chattering group. In bear country, I prefer to occasionally whistle in low visibility areas rather than wear an annoying bear bell to alert oncoming wildlife of my presence. Annoying photographers like myself have to take photos of everything, and noisy humans along the trail will always intrude with their friendly banter and passing presence. I would much rather hang out with the marmots and pikas or anything else not human. I prefer the company of critters and my wife. But on this trip, starting out at first light, I was determined to find wild caribou.

During a visit earlier in July, I looked at a stuffed, taxidermic, young caribou in Alberta’s Banff National Park visitor’s center at Lake Louise. The signs informed readers of a ‘species at risk’ and of an unfortunate avalanche in 2009 that killed many of the woodland caribou in the park. The visitor’s center signage described the rapid decline of the iconic species. Labeling it a ‘threatened species,’ which despite living in a National Park, has been loosing out in every human management decision. Historically, the range for mountain caribou extended much farther east of the National Parks, but rapid industrial growth has eliminated caribou range and pushed the species entirely into the Parks. Re-introduced elk populations in 1920, for the ‘public enjoyment,’ have also exploded along with the simultaneous slaughter of predators known as ‘predator control’ programs into the 1950’s. Since then, wolf numbers have bounced back and they now enjoy an elk buffet. Before human interference, wolves had no access to caribou because of deep snow. Now they follow logging roads and convenient, packed down, ski and snowshoe trails into the mountains through critical caribou habitat, leading them to easy winter kills. Unfortunately, such poor management decisions have led to wolves unjustly receiving the blame for predating on caribou.

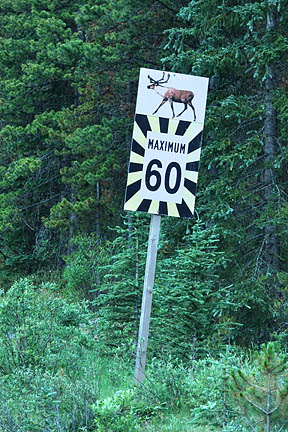

Habitat loss, logging, road collisions and human disturbance during winter recreation have all played their destructive roll. Both the Banff and Maligne herds, two of the five resident herds in the Jasper/Banff area are already gone, Banff’s caribou were extirpated in 2009. Ironic caribou warning speed limit signs remain where road accidents were once common near Maligne Lake. One nearby woodland caribou herd roam the Tonquin Valley which predictably have numbers far below a self sustaining level, estimated at 38 individuals in 2019. Parks Canada has looked into captive breeding programs and reintroduction but seems delusional in thinking it can bring more caribou into already compromised areas. With split interests in winter recreation, and conservation, ecological integrity of the National Park does not seem to be the priority. Always considering caribou an ice age species, I admired early Paleolithic art in books depicting giant antlered reindeer drawn in bold charcoal black and reds on European caves. In 1995, I cut out an article in the Denver Post about the newly discovered Chauvet Cave in France with 30,000 year old artwork of numerous animals including a complete ‘Reindeer Panel’ drawn in rich charcoal. My interest in caribou was peeked in 2004 after looking at old black and white photographs of my wife’s family and friends hunting barren-ground caribou in Alaska during the 1950’s. White bordered photos with decorative edges show the hunters including Anna’s mom, Ginny, along the Nilchima River on the Alaska tundra. The hunters had their ‘swamp buggy,’ an off-roaders dream, in the background while cleaning their caribou and standing next to the animals with their huge, multi-branched antlers. The relic, ice age looking animals with their twentieth century big game hunters made me think of their Stone Age equivalent thousands of years ago wandering the edges of the glaciers with nearby grazing mammoths.

During our July visit, after browsing the Jasper Public Library used book sale, I searched for information on the local caribou. I found old books with black and white photos of small herds and statistics of dwindling numbers. A Canadian wildlife highlights book suggested 'The rare woodland caribou can be seen during the winter along the Maligne Road and Icefields Parkway.' The Maligne herd, once at a paltry 60 individuals, down to 5 in 2016, now zero. In the 1960’s Jasper had hundreds of caribou, now there are fewer than 60 left. Looking online, It looked like the best chance to catch a glimpse of a woodland caribou would be in the Tonquin Valley, a hike over 23 kilometers one way in the Trident Range of the Canadian Rockies towards the Amethyst Lakes.

The next day after my research, Anna and I ran over twenty kilometers, over 12 miles round trip along the Portal Creek trail towards the Tonquin Valley. After arriving at the first campground, the rough trail and our aching feet subtly suggested we turn around. I hiked a bit further past the Portal Creek Campground and scanned the distant slopes of Oldhorn Mountain near Maccarib Pass for any potential wildlife movement. Nothing but open meadows, rocky cliffs and a crystal clear sky. Turning back, we later explored the Mount Edith Cavell area and other potential spots with no luck. At that point, I vowed to return and make it all the way to the Tonquin Valley and Amethyst Lakes. Now September 6th at first light, I have loaded up rain gear, umbrella, warm winter clothing, stove, tent, 0ºF sleeping bag, two sleeping pads, a heavy bear proof canister full of food, water purifier, water bottles, bear spray, camping permit and additional photographic equipment. Sitting the heavy pack on my truck trail gate, I looped my arms through the straps and hefted my overloaded backpack onto my back. With long baggy pants and a long shirt on to defend against the inevitable mosquitoes, I donned my wide brimmed hat and set off on the muddy trial. Signs at the Tonquin Valley trailhead stated ‘You are in caribou country’ and ‘Jasper’s caribou are disappearing at an alarming rate.’ Other signs suggested avoiding caribou range during caving season (June and early July) and mating season (late September). Since it is the first week of September, this trip fit those requirements. The trail dove into thick subalpine fir forests with branches draped in gray arboreal lichen blowing in the light, cool, breeze. During our earlier visit, delicate, yellow Columbine flowers, blue and lavender colored, shrubby penstamon and white bunchberry dogwood with four, little, white petaled flowers lined much of the trail. Now, a few dogwood flowers and worn out yellow daisies occasionally dotted the path as I began to warm up climbing higher into the forest. I removed my jacket and strapped it on top of my pack as I hiked southwards through the shaded river valley. Round river cobbles covered with moss lined the edge of the shaded trail as I crossed the wooden Portal Creek Bridge over loud, turbulent waters. It was a cloudless sky and a bit smoky from the forest fires, but the sun was out and it wasn’t raining!

Chokecherry bushes and small alder trees grew near the trail as I hopped over small creeks while traversing the undulating trail. I started to increase my pace, comfortable with the packs weight distribution and having no problems with the feet. Soon, a pointy Mount Peveril rose over the path as I crossed another wooden bridge over a tumbling Circus Creek. A few more kilometers the trail paralleling the churning waters began to climb out of the trees into a rough scree field or boulder covered area. A quick, high pitched ‘chirp’ echoed out of the rocks as I stopped and searched the rocky hillside. Soon a pair of tiny rock rabbits or pika, popped their heads out like ‘wack a moles’ and skittered across the lichen covered boulders. About the size of guinea pig, the little brown critters would zip behind one rock and appear on top of another with a loud ‘chirp!’

While hanging out with the pikas, I took a few photos as clomping and clunking sounds soon echoed over the rocky trail. Staying out of the way and off the trail, it was about 9:15 AM, when a group of nine horses with four riders complete with cowboy hats passed noisily through the boulder fields with their luggage trailing behind them on a string of horses. Horses certainly make a racket and left unpleasant and smelly areas on the trail. Surrounded by tall mountains, a pyramid shaped Lectern peak rose off to the east as I descended back towards the creek, where small patches of colorful wildflowers painted the side of the path. Thick fir forests began to thin out and patches of willows followed the lush river valley. Around lunch time the jagged wall of the 3,112 meter high Mount Erebus rose in the southwest as I arrived at the little campground with a couple of picnic tables and a few spots for tents in the trees. Carefully un-hefting my heavy pack onto the picnic table, I felt a breeze instantly cool my sweaty back as I pulled out PJ sandwiches and bean burritos. Shoving food in my face, I quickly inhaled lunch and washed it down with my remaining water bottle mixed with scoops of powdered, sugary goodness that is Gatorade. Sliding the tent and poles out of the pack, I found a slightly sloped, flat spot in the trees and kicked away any remaining rocks, pine cones or back stabbing debris. Laying down the protective tent footprint, I snapped together the poles and set up my two person tent and threw in my sleeping bag and pads.

Remembering the bear tracks along the trail near here the previous July, I walked away from the tent area and hoisted my pack holding the heavy bear proof ‘Counter Assault Bear Keg’ food storage bin with more lunches, oatmeal, dried vegetables, noodles, dried potatoes, dried fruit and cliff bars up an old west gallows of sorts. The Park aptly calls it a ‘bear pole.’ Pulling the rope, the pack rose near the highest point on the oversized sawhorse, dangling in the wind like a giant piñata for hungry bears. Afterwards, I walked to the creek well away from camp and pumped cold water through the filter into my water bottle. Zipping up the tent, I headed out in the clear afternoon with fresh, cold mountain water in my bottle and my camera. Still hiking south, I felt super light without the portable house on my back. Since I arrived at the campground early, I could now explore the surrounding area. Following the trail towards the river, the bridge had been washed out by flooding. I found a good spot just upstream to jump from boulder to boulder to the cross the creek. Passing the horse parking and rest area, I continued into wet meadows chewed up by horse traffic. Jumping from rock to rock to avoid thick mud, the terrain and elevation began to change again, from willows and pine trees to more of an alpine tundra as the trail climbed more steeply. Turning west towards Maccarib Pass, smoke was much more visible. Dry grasses and fall wildflowers were mixed in with low shrubs turning red and yellow.

Banded yellow, orange and brown, Millbert’s tortoiseshell butterflies enjoyed the nectar of light blue aster flowers. Deep orange Fanus anglewings and Northern blues fluttered around the remainder of summer’s flowers. Tailed blue butterflies would sip the nectar of northern sweetvetch as wild bees would nuzzle yellow, subalpine daisies. Near the top of Maccarib Pass bumblebees would bounce through the pink blossoms of fireweed. Pointing the way up the mountain, a small vesper sparrow with a thin white eye ring perched on a cairn, a pile of stacked stones marking the trail. Lying at the base of another cairn marking the top, a small scratched up, brown sign with yellow lettering stated ‘Maccarib Pass Col Maccarib 2057 m.’ Must be an old sign as the current elevation maps put the pass over 2200 meters, over 7,200 feet.

Unfortunately, hazy skies filled every view as I continued to search the mountain hillsides for any wildlife. Looking west over the pass, thick smoke almost completely obscured the rugged Ramparts. Stretching a bit while having a snack, it was past 3 PM, time to head back down the mountain towards camp. It felt good to run down the trail as I passed the pink fields of fireweed and little bearded wizards of the Western anemone or wind flower with coned headed flowers dangling feathery and shaggy beards that blew in the breeze. Popping out of a fir tree, a red breasted nuthatch watched me trot past. Descending into the valley, a yellow-rumped warbler hunted for insects in a willow tree near the creek. More colorful butterflies enjoyed the flowers as I passed through the mud zone and hopped across the river back to camp. Lowering and raising the food piñata again, I cooked up dinner, cleaned, filtered more water, greeted new human arrivals, brushed the teeth and washed off in the creek, the cold water feeling great on my feet which made it to Maccarib Pass and back, over 15 kilometers today. Looking at maps, reviewing digital photos, I relaxed a bit and hoped the good weather would hold, as rain was in the forecast. Before bed, I used the posh facilities behind the trees climbing up a few steps to a small open platform housing a toilet seat over a raised storage barrel. Great view, however, I would not want to be the pack animal carrying out that hazardous waste. Lying on top of my sleeping bag, I listened to the light gurgle of the creek as the low murmurings emanating from my tented neighbors slowly quieted. Wide awake at 4:30 with a clear sky, I set up my camera from my sleeping bag just outside the tent hoping to capture any sign of the Northern Lights over the peaks. Just a few clouds drifting by. Stars glittered over the hazy mountains.

Rising before the morning light, a massive, full, orange moon rose over silhouetted pine trees and the distant ridge line. Unzipping and zipping noisy zippers, I crawled out of my sleeping bag and tent to scan the surrounding area with my headlamp, searching for any potential eye shine. Standing up, I spun my sleeping bag around, airing it out like a giant windsock. Quietly as I could, using moonlight and occasionally my obscured headlamp, I walked away from my tent, lowered my dangling food piñata, packed the sleeping bag and set up my stove, cooking oatmeal for breakfast on the picnic table next to the trail. After cleaning up, I folded the aluminum poles, tent, and ground cloth as the other neighboring campers continued to sleep. Anxious to get on the trail, I loaded up my pack as I admired the full colorful moon again. One final check of the area - nothing dropped or left behind - bear spray on my hip and I was on my way. I’m a big fan of ‘leave no trace.’ Locating the trail in a low morning light, all my senses were on alert as I turned my headlamp on. Having nearly memorized the path to Maccarib Pass, I quickly navigated the wilderness obstacle course with grabby branches, wet rocks, deep mud, and rushing water as I quietly sang ’She’ll be comin’ around the mountain.’ I weaved through the willows to where the pine trees began to thin out. Climbing the pass again, I looked down on the creek, now reflecting a light colored sky surrounded by dark forests with jagged blue mountains on the distant horizon and the moon nearly down over the rocky ridge. Now much more open, I was able to see the trail and any potential traffic so I turned off my headlamp. Enjoying the cool air and spectacular surroundings, I quickly hiked up to the open tundra where an orange sun was rising. Near the saddle of the pass, a fuzzy, chubby and brown, hoary marmot perched on his dirt covered burrow mound as he looked out over his front yard filled with fields of pink fireweed. Now descending into new, unexplored territory, I picked up the pace while still scanning the hillsides for any movement. The foliage began to grow thicker the lower I hiked. Almost perfectly camouflaged, a few speckled, white-tailed ptarmigan walked through multicolored grasses while pecking for food among the low branches of light green and yellow leaved mountain mahogany.

As the valley leveled out, large boulders covered in black, white and brown lichen remained in place after being dropped by massive glaciers and now were surrounded by low, green shrubs. Small rivulets of water wandered into the willows. After 8 AM, a group of five friendly backpackers of men and woman wearing earth tones were hiking up the valley. I said ‘hi’ and asked the passing group if they had seen any caribou, they said no. We also briefly exchanged our negative bear sightings. Further in the tall willows which seemed like a perfect place for a bear ambush, I whistled and hummed the soundtrack to the Adams Family. In a clear area, a perched northern harrier took a break from strafing the willows and glared at me as I passed.

The trail began to get muddier again as another backpacker approached. I asked her my same caribou question and her response was better. Initially she said no, but other hikers had seen some a couple of days ago in the trees north of the campground. Also buoying my spirits, I began to find big caribou tracks on the muddy trail after arriving at the Maccarib Campground junction near a boulder filled Maccarib Creek. The tracks had no boot or horseshoe marks over them, a clear indication of recent travel. I slowly walked the trail scanning through the disperse fir trees and moss covered rocks. The next two trail junctions had more brown and yellow trail signs bolted to fir trees with arrows pointing to the nearby campgrounds, lakes, backcountry lodges, and various trailheads. More clean caribou tracks appeared in the goopy trail just a few kilometers from Amethyst campground. Caribou were maddeningly close, I just couldn’t see them. Graded layers of silhouetted fir trees were obscured by haze as the nearby Clitheroe Peak was almost completely hidden in a thick blanket of smoke which filled the entire Tonquin valley. The jagged Ramparts, showing only a few snow patches were silhouetted in the shroud as they loomed over the colorless, gray pools of the Amethyst Lakes. A well worn path paralleled the waters edge as I approached the campground with a group of six young backpackers intent on making tracks, no time for small talk. Arriving at the Amethyst campground around 11 AM, I was ready to loose the weight and found my tent spot. Quickly setting up camp, I fished out lunch and packed my gear into one of the many metal ‘bear safe’ lockers. Having performed the feeding, bear proofing, and housing rituals I went on the search again and backtracked along the trail a few kilometers to where I had seen the caribou tracks in the mud. A light breeze blew ripples into the pair of lifeless Amethyst Lakes, each about two kilometers long. Usually critters snooze during midday, so it's not the best time to search for wildlife. Having discovered the same tracks and not much else, I turned back towards the campground and continued past, heading southwards towards the Surprise Point Meadows, another few kilometers. Nothing but smoke. These elusive critters really were ‘gray ghosts.’ Still hopeful, I slowly walked back to the campground and organized snacks and meals. Heading out in the afternoon about 2 PM, I hiked south again passing a small room sized fenced off area with a sign ‘An Eye on Ecology,’ the National Park’s long term study on soil and vegetation trampling from humans, wildlife and horse grazing set up in 1996.

They finally materialized in a distant meadow near the tree line, moving slowly through the smoky haze. Grazing side by side with their heads down, a pair of big, male, woodland caribou, part of the southern mountain herd, mowed the lawn with their massive antlers gently bobbing in the air. The scene was quite surreal as I carefully and quietly walked the trail towards a pair of shapes in the distance, not quite believing they were actually there. Having no idea if they would spook and bolt, I shot a dozen photos at ten frames per second as they moved down the hillside. If you weren’t paying attention, one could mistake the two for a pair of horses calmly grazing. Walking off trial, I approached a large, three foot tall boulder, another glacial erratic. Leaning down on the smooth granite boulder, I zoomed in and photographed them individually as they walked closer to me, grazing westwards. I was in clear view and they could have cared less. Keeping my distance, I took off my camera pack and sat on top of the boulder over 50 yards away. The 600mm reach of the lens did a great job of filling the frame with magnificent animal and there was no need to approach them. White tips of cotton grass bounced back and forth in a constant breeze. The more mature male with larger antlers walked towards the lake as the other male grazed near the gray boulders higher in the meadow. Ten minutes later, boulder caribou laid down and relaxed, obviously not disturbed by my presence. Shooting close-ups, medium and wide angles of both video and photos, I eventually just sat and watched them wander aimlessly, enjoying the bug blowing breeze between the lakes.

Usually found in small groups, woodland caribou have gray/brown fur with a whitish neck and mane with males weighing in at nearly 600 pounds. Females also grow antlers and usually give birth to one calf a year. They feed on slow growing lichens, grasses, sedges, shrub leaves, herbs, and mushrooms and in winter, on arboreal lichens that dangle from branches in old growth forests and sometimes willow and birch twigs. They migrate from high alpine areas in summer to old-growth subalpine forests in the winter. Evolving to survive in deep snow, their large, rounded hooves are able to splay out like snow shoes for good winter travel as well as good weight distribution for boggy summer tundra. They are also good swimmers, their air filled hollow coat hairs giving them extra buoyancy. After another ten minutes of watching, a lone hiker on the trail drifted over. I quietly said ‘pull up a rock and enjoy the show.’ These caribou must have been somewhat habituated to humans as they continued to nap and graze the breezy spot. A small flock of four feeding ducks floated along in the nearby pond, bobbing with bottoms up in the rippled waters. Quietly we watched and occasionally took photos. I also took the time to review photos and videos to make sure my settings were correct and focus was sharp. After an hour another pair of hikers joined us on the boulders. Keeping the camera out, I slowly headed back to the trail to see If there were any other friendly caribou in other areas as I walked to Surprise Point meadows. Having found nothing, I returned to the boulder field, now, without humans, just the caribou moving closer to the tree line. The orange sun was now nearing the knife edges of the Ramparts as I watched the grazers wander about the boulders, fir trees and finally disappear into the thick forest as if they had never been there. It was a privilege to be able to watch such amazing animals for over two hours in such a beautiful area. Touching the jagged peaks, the orange orb gave off barely any light as its reflection wavered in the dark, rippling waters.

As I hiked the path past the lakes, thick, smoky fires cast everything a yellow, orange hue. It was such a dramatic change from July, when the sky and scenery were crystal clear. Returning to the large Amethyst campground with many more sites than the previous night, there was much more activity as hikers talked loudly and hung out in groups at the picnic tables. A neighboring family with kids clanked poles and metal stakes while yelling at each other as they fought with their tent. Ah, humanity! I prefer the caribou who were much quieter.

After finishing dinner, the family was still squabbling as I put my headphones on and tried to relax in the tent, away from the mosquitoes while I looked at caribou photos in the camera. I had lucked out on the weather too, as rain was predicted for this week. Having hiked over 24 kilometers today, much of it back and forth over the same territory, I still felt strong. I debated what to do as I had a second night reserved at this spot. If it rained, the already goopy trail could turn into an ankle breaking mess not to mention there’s nothing worse than sleeping in a downpour praying water doesn’t flow into your sleeping bag. I would let the morning and the caribou decide. If I found them again in the morning I would stay and if they weren’t there I would go. Ecstatic about the days encounters, I filtered water, brushed the teeth and hit the sack. I kept my headphones on as numerous conversations floated through the smoky air. The sky was growing brighter but I still needed my headlamp to see around camp. Trying to be quiet, I retrieved my pack from the metal safe, releasing the noisy door latch with a loud ‘clank’ and set up the stove and boiled water for breakfast. It had rained a bit during the night and the tent was wet. A few early birds were up, dark silhouetted figures with headlamp lit faces bobbing through the trees beelining towards the facilities. Wearing my light down jacket, winter hat and fingerless gloves during the chilly morning, I wolfed down oatmeal, raisins and honey o’s, I cleaned the dishes, I packed up the kitchen, and went to see what the caribou had decided. Only hiking a few minutes led me to the boulder filled, grazing meadows. I carefully scanned the area, but no one was home. I apparently had used up my visiting hours. Time to go. Airing out complete, the sleeping bag and pads were successfully crammed into the pack as I dried the outer rainfly with a used sock. Un-staking the tent and lifting it into the air, I shook any dirt from inside as well as some of the remaining moisture. Removing the cold aluminum poles, the tent settled like a miniature, partially inflated hot air balloon. Folded poles, deflated tent, mud cleansed stakes slid into their thin nylon sack. I cleaned off the wet dirt sticking to the bottom of the tent footprint, rolled it up and sacked it as well. Snacks and lunch were relocated to easy-to-reach pockets as I hoisted my pack in the hazy morning sun. The air smelled better than the previous day and the trail hadn’t turned into complete goo. The one thing I had neglected to think about was my current camp site at Amethyst was reserved for tonight, not a site at Portal Creek Campground. That would be reserved for the next night. With caribou still on my mind, I was ready to continue the search, this time, only in one direction, towards home. As always, with bear spray on the hip I rolled out onto the trail. Walking along the calm lakes, I scanned for any footprints that remained in the mud. Mostly horse and human. Enjoying the cool air, I watched the edge of the forest and made good time to Maccarib Campground where residents were eating breakfast. No caribou or bears. Passing through the willows and quickly gaining elevation I watched a Cooper’s hawk perched in a gray skeleton of a dead fir tree overlooking the willows. The sky, already moody began to darken as I had a drink and a snack. Cruising past the cairns on the pass, a light rain began to fall, not enough for rain gear, but a warning of things to come. As I descended past the marmot and his fireweed filled yard, there were no bees or butterflies, just a steely gray sky ready to burst. Sensing a deluge, I picked up speed, moving quickly downhill through the alpine tundra, into low fir trees and finally into the willows along the creek. Passing through the muddy meadows I arrived at the Portal Creek Campground just as a heavy rain began to pour. I popped up my umbrella, proud I remembered to bring it. Sweaty hiking in rain gear is the worst. Continuing past the campground, I told myself 'might as well go all the way.' Climbing up the rocky scree trail wasn’t to bad as most of the trail was packed rock. No pikas chirped this morning, however I remembered last July, a family of Clark’s nutcrackers squawked and raised a ruckus along this stretch of trail through the boulder field.

Wet branches of dried and dead fir trees filled the air with a wonderful pine aroma. Enjoying the cooling air, the trail began to turn slippery as I made it to the cover of thick forest. At least the overhanging fir trees gave the trail a little more protection from the elements. Cruising downhill again along the Portal Creek, the trail began to turn into a quagmire. I passed over a saturated Circus Creek bridge as a large group of backpackers was just starting out in the rain, already looking like wet dogs in their rain gear, miserable, water ran down their faces as they sloshed through the muck. Trotting downhill through the easy stretches ate up distance quickly and I was soon crossing the Portal Creek Bridge, passing the few remaining white flowers and mossy rocks. After a fast 21 kilometers I was back at the parking lot. ‘Where were my keys?!’ Digging through camping gear I found them on their special plastic hook. Unlocking the tail gate, I threw my pack in the back of my old 1992 Toyota pickup. Changing into some different socks and running shoes, I was anxious to get back to a comfortable bed after almost a month on the road. I'd been sleeping in the truck since the August solar eclipse in Jackson Wyoming, through Yellowstone, to Alberta, through British Columbia to Haida Gwaii and now back home to Denver. Having skipped two days of wet, rainy, and muddy tent camping in noisy campgrounds was a relief. Despite the thick smoke, it was a very successful trip - it was a thrill to see such an iconic species! The mileage roundtrip backpacking was over 60 kilometers or over 37 miles in three days, not bad! Many of those miles were with just with a light camera bag and water. And not one bear to be seen on the trail, not even a track in the September mud. Thankfully, for all my years of backcountry travel in bear territory, I’ve never had to use my bear spray.

Stop reading here if you don’t want to read any more of a depressing story. Driving south on the Icefields Parkway past Jasper’s Athabasca Glacier, thick smoke from British Columbia’s forest fires blanketed the spectacular peaks, glaciers and vistas. All the way through Montana, heavy smoke plagued my travel and unfortunately, it now seems, this is the new normal. Some time after arriving home I found some unfortunate, disturbing news. Now, all caribou are extirpated, gone, from the lower 48 states. This was a species that had survived the ice age, even as massive glaciers retreated northwards, the caribou had wandered across the northern United States where Native tribes hunted them for thousands of years. In January, 2019, Idaho’s last few surviving caribou from the Selkirk herd were flown to British Columbia to a pen, where they were held before releasing them to another herd of caribou farther north. According to Gregg Servheen, Idaho Department of Fish and Game Wildlife Coordinator 'These caribou were a native species of Idaho. We’ve lost a native species.' Fighting an uphill battle, the January relocation ended 35 years of attempted caribou restoration. Similar problems plagued Idaho’s Selkirk herd; logging and roads since the 1950s, brainworm disease spreading from deer attracted to newly clear cut areas, predating mountain lions and wolves following the deer and roads, wildfires and snowmobiling in caribou habitat. Even some Idaho locals never appreciated the charismatic species because of perceived impacts on their local winter economy. Residents protested snowmobiling closures in remote caribou habitat few could even get to. In books, various mammal species maps show one tiny finger of caribou distribution in Idaho. Knowing this, that there was one small population of caribou in the lower 48 was somehow reassuring. Despite never getting the chance to see them, I was so disappointed the United States couldn’t maintain its wild herd of woodland caribou. Why was the media coverage almost non-existent over the loss of such an iconic species? Did people see the herds of barren-ground caribou in Alaska and say ‘good enough’? With caribou extirpated from the lower 48 states, I wonder how Canada will continue to manage their remaining and declining herds? It's a battle of economy versus conservation. Inevitable climate change with more droughts, fires and extreme weather will affect not just caribou, but all species including us. After watching narrow minded responses by politicians who continue to lie, blunder and blather over Covid-19 and global warming, I think it is a foregone conclusion all worldwide species numbers will continue to decline and then eventually for many, boop - gone.

As I write this, massive droughts now parch the west and the forests around our home in Colorado are going up in flames. Today, my hometown of Denver, Colorado is the most polluted city in the world from drifting Colorado, California and western wildfire smoke. We all need clean air to breath and clean water to drink, yet humanity plows ahead in ignorance and blind ambition. It makes me so mad the needless greed and shortsightedness of those who continue to deny and destroy for money and power. For our part, my wife and I have worked in renewable energy for decades, eat plant based diets, shop mainly at second hand stores, employ solar energy, harvest rainwater and maintain a small home footprint which counters some of our carbon producing travels. Despite trying to live sustainable lives, I believe the arrogance and stupidity of decision makers and willfully ignorant voters will continue to prevent any real response to climate change. As the gray ghosts follow their namesake into extinction and more species disappear, the pessimist in me wonders, how long it will it take the human species to destroy itself?

|

Destinations in the Gallery

All contents copyright ©Dave Parsons

DP Home | Feature | Gallery | About